Missing and Murdered Indigenous People crisis is a century-old problem. Akey Ulteeskee's story proves it

Written By Sarah Liese (Twilla) | KOSU Radio

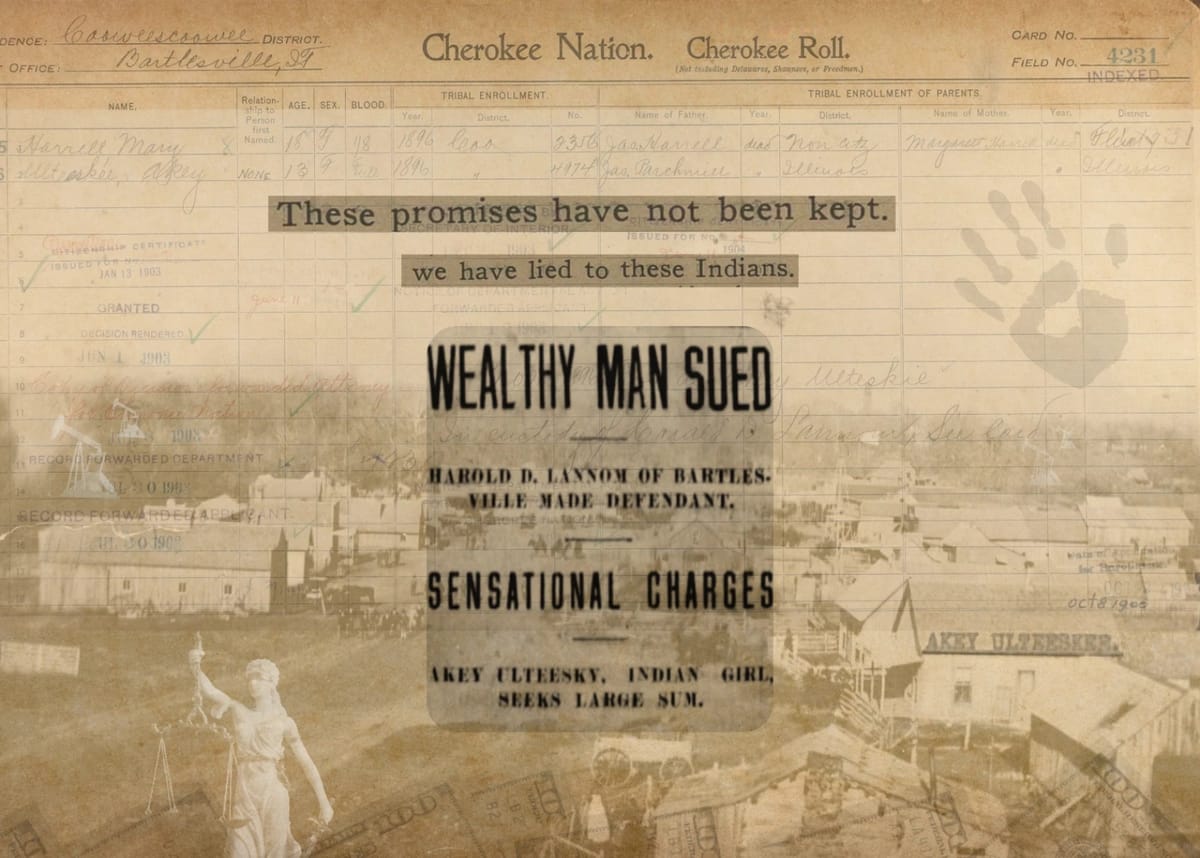

Mainstream media outlets have often overlooked stories of missing and murdered Indigenous people for more than a century. The story of Akey Ulteeskee, a Cherokee woman who suffered sexual and financial abuse at the hands of her alcoholic guardian in the early 1900s, highlights a glimpse into the history of this issue and how the fight for justice — despite its lengthy history — continues for Indigenous relatives.

This reporting was supported by the International Women’s Media Foundation’s Fund for Indigenous Journalists: Reporting on Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, Two-Spirit and Transgender People (MMIWG2T).

At just 4 years old, Akey Ulteeskee became an orphan.

The year was 1891, a fast-changing time for American Indians and Ulteeksee, a young Cherokee girl living near Fort Gibson in Indian Territory. Pressures to dismantle tribal governments and how they cared for their people were on the rise, leaving tribal citizens, such as Ulteeskee, vulnerable.

It had been less than five years since the Dawes Act was put in place. This federal policy meant that government workers, who looked nothing like Ulteeskee, would arrive in her community in northeast Oklahoma and begin listing her relatives and their blood quantum on the Dawes Rolls.

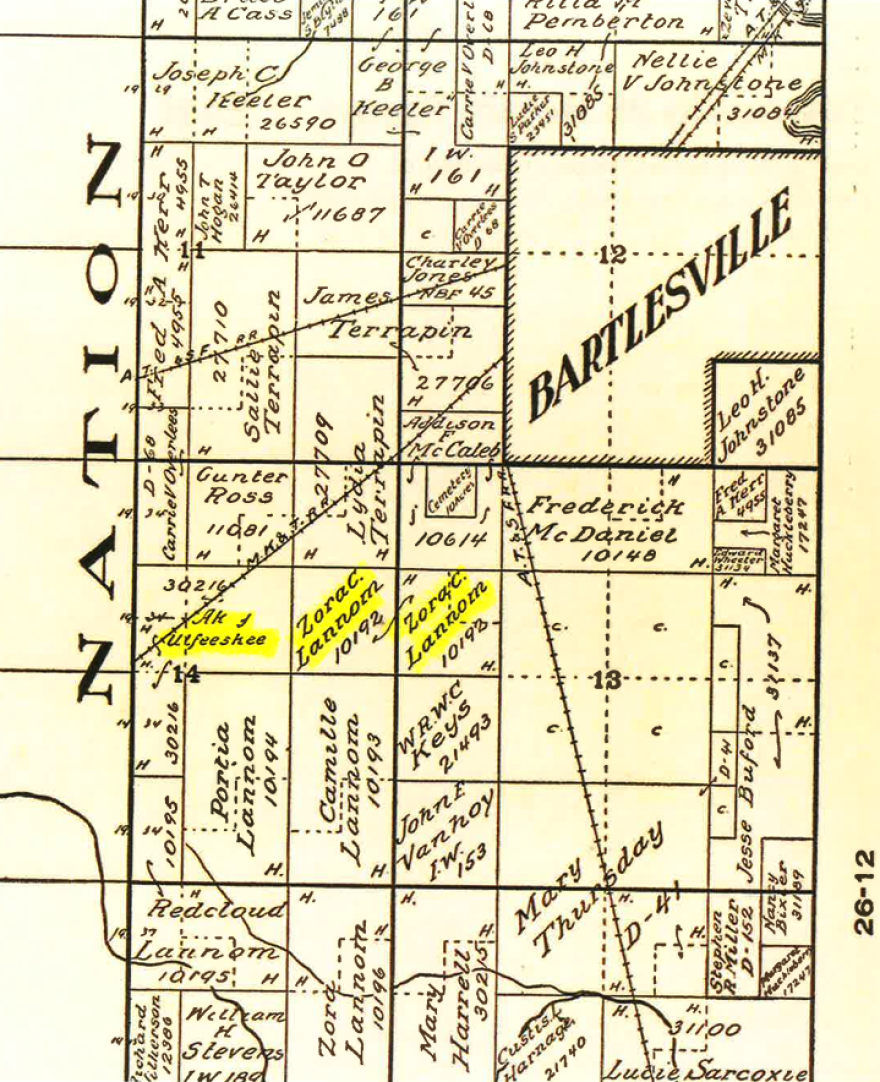

Their communal lands were then divided into individual plots, often called allotment lands, forcing a new way of living and thinking about land for the Cherokee and other Indigenous peoples living in what would become known as Oklahoma.

With those individual parcels often came money because the land could be leased or oil might be discovered beneath the surface. But because of the Indigenous wealth beginning to sprout, other people tried to gain control of the land through any means necessary: murder, outright theft, or, as was the case with Ulteeskee, guardianship.

The exploitation that took place more than a century ago persists today; it just goes by a different name: the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls and Two Spirit crisis, or MMIWG2S.

Ulteeskee and another Cherokee orphan, Mary Harrell, would be given allotments next to what would become their new family, the Lannoms. Both girls are listed beneath the Lannom family in the Dawes Rolls, a symbolic fact that foreshadows how they were later treated by their so-called “caretakers.”

Ulteeskee dealt with abuse and manipulation in her lifetime — as a result of the Lannoms’ neglect. Mary Harrell lived with a Lannom in Arkansas, until later she was sent away to the state’s mental institution.

Within the Five Tribes — the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Seminole, and Muscogee Nations — 1,200 cases like Uteeskee’s contained evidence of fraud and financial abuse at the hands of guardians. These guardians were appointed by the federal government so that Indigenous people wouldn’t have their wealth from their land, oil or minerals stolen. But that often backfired, according to thousands of cases documented by the Indian Rights Association, an organization formed in the wake of the allotment period to advocate for Indigenous people.

Abuse and exploitation still exist in the MMIWG2S crisis. Despite the issue spanning more than a century, many Indigenous people continue to go missing or wind up murdered as a lasting result of exploitation that continues to this day.

Indigenous people fell victim to a system ‘tainted with fraud’

When driving through the Cherokee Nation in the winter of 1889, Zora and Harold Dixon Lannom discovered Akey Ulteeskee, who was described as “poorly clad” in a 1904 news article from the Humboldt Herald. The Lannoms decided to welcome Ulteeskee into their home, which also came to include all of their children: Camille, Portia, Red Cloud and Marguerite “Zora.”

Oklahoma State University History Professor and Head Brian Hosmer said Ulteeskee was a prime candidate for a guardian, such as Lannom, whose incentive became clearer with time.

“An orphan would be the kind of person who was placed under guardianship fairly early,” Hosmer said. “...There's a greater incentive, if you want to think about it, for people to become guardians once property is in play — that changes the incentive structure.”

![The Lannom mansion, also known as "Belle Meade", burned down in 1926, with "seven people narrowly escap[ing] with their lives," according to the Bartlesville Examiner Enterprise. The mansion had 26 rooms and was built by the same architect who built Frank Phillips's mansion, according to an interview with Joe Barber conducted by the Oklahoma Historical Society.](https://npr.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/bd75439/2147483647/strip/true/crop/3191x2031+0+0/resize/880x560!/quality/90/?url=http%3A%2F%2Fnpr-brightspot.s3.amazonaws.com%2F2f%2Fa7%2F7254c47d461ca7b1ac4d3ab13663%2Flannommansion-okpc2101front-600.jpg)

The Lannoms selected their allotment lands near Bartlesville and established their status as a wealthy family, owning a 26-room mansion. Although some of the wealth came from Ulteeskee’s allotment lands, most records show their affluent status did not extend to Ulteeskee or Harrell.

A 1912 investigation by the Bureau of Indian Affairs revealed that Lannom, Ulteeskee’s guardian who managed her finances and allotment lands, sexually and financially exploited her. Lannom forbade Ulteeskee from attending school with his biological children, who became well-educated, and forced her to act as a servant when her lands produced more than $20,000 — about $663,000 in today’s dollars.

Warren Moorehead served on the Board of Indian Commissioners, an agency that advised the federal government on policies related to Native Americans from 1908 to 1933. He published a book titled Our National Problem: The Sad Condition of the Oklahoma Indians in 1913, highlighting fraud in guardianships within the communities of the five tribes. His book can be found in the database of the Indian Rights Association (IRA). It reveals that many conservatorships, intended to help American Indians manage their finances, were disastrous.

“In and about Sapulpa, there are nearly 1,200 guardian cases, a large proportion of which are tainted with fraud,” Moorehead wrote in Our National Problem. “…I am informed that in Tulsa County, there are some 300 guardians of minors’ estates or administrators of incompetents, who have not filed complete records or are delinquent in their records. Numbers of these guardians have never filed any reports whatsoever.”

Like Moorehead, Hosmer said Ulteeskee’s situation was not uncommon. What sets her story apart from many others, though, is the BIA stepping in to conduct their own investigation and take Lannom to court.

Hosmer said the BIA may have become interested in Ulteeskee’s case due to a public divorce between Harold and Zora Lannom in 1910, a time when women’s rights were significantly limited.

“Mrs. Lannom had secured a divorce charging extreme cruelty, drunkenness and failure to provide… at a time when he had vast oil holdings in the oil district,” an article from the Daily Oklahoman said on October 7, 1912.

The article shared that Harold Lannom’s ex-wife, Zora, advocated for him to have his own guardian for fear “he would squander all of his money.” The newspaper also chronicled how Harold started to spiral out of control, including when he followed Zora to her second wedding in California and, while there, threatened to shoot up a saloon.

Though Zora was able to escape him and start a new life, Ulteeskee stayed with Harold after the divorce. He then raped her, and she became pregnant with his child, according to a passage in Moorehead’s book.

Ulteeskee, then 24, delivered her baby girl in August of 1911 near Saint Luke’s Hospital in Kansas City. Records reveal that Harold Lannom brought Ulteeskee to deliver her baby in the care of a deceptive doctor, who engaged in identity theft. The doctor’s real name was J.M. Martin, but he operated his practice under the name Dr. F. W. Lanoix, the name of a deceased physician who built up a reputable practice.

Days after delivering her child, Ulteeskee was forced to hand the baby over to a wealthy family residing near Kansas City. She never met her daughter.

The BIA intervened and took Lannom to court to attempt to claw back the money he stole. But the system — built on broken promises and perpetuating the exploitation and violence — did not radically change. As a result, many Indigenous people continue to face similar mistreatment today.

“All these abuses happen, but somebody has to actually seek redress,” Hosmer said. “Otherwise, they just continue to happen as was happening here.”

MMIWG2S is more than a century old, so what’s been done about it?

Lorenda Morgan received a call in 2015 that her cousin, Ida Beard, didn’t return home from a friend’s house. Beard’s mother was looking for her.

“She's not like somebody that has traveled the world or even hardly left the state or even the area of El Reno,” Morgan said. “She's just a very hometown girl who stays close to her mom and her kids.”

Morgan described Beard, a Cheyenne and Arapaho citizen, as a comedian. She said Beard cared for her mother, who had become blind by the time Beard attended high school. Beard and her sisters chipped in to help drive their mother and offer help when they could.

“And so I think that's what made her case kind of interesting, that there hadn't been any movement on it,” Morgan said.

She said law enforcement did not prioritize Beard’s case and made assumptions during interrogations with family members about Beard’s lifestyle. Maybe she had a new boyfriend? Maybe she was just staying out with friends?

“My mom said, ‘They [law enforcement] talk to us like we done something,” Morgan recalled. “So I told my mom, ‘I will go over there. I'll talk.’”

Morgan said the detective interrogated her and approached the situation with a bad attitude, later raising his voice at her. So she decided to start posting on Facebook about her cousin’s disappearance, which caught the eye of her friend and state representative, Mickey Dollens (D-93).

Dollens used his media influence to shed light on Beard’s case, draft legislation and create an interim study to bring MMIWG2S, also known as MMIP, to the forefront. Eventually, Dollens' teamwork with Morgan paid off, and Ida’s law was passed in 2021, which helped create a liaison office at the Oklahoma State Bureau of Investigation dedicated to MMIP cases.

“One of the reasons that we talked about having this [MMIP] unit at the OSBI was to help with some of these cultural differences and also with police training,” Morgan said. “Every database is different. …And so, that's what Ida's Law was created to do, to work on some of these things and to help liaison for families if needed.”

A lengthy history of policies and laws designed to bring justice to families precedes Ida’s law, including the General Crimes Act of 1817 and the Major Crimes Act of 1885. Those criminal acts, respectively, granted federal jurisdiction over crimes in Indian Country when there is a non-Indian victim and when a major crime, such as murder, occurs. The Violence Against Women Act and its reauthorizations have helped provide funding for victim services and widened tribal jurisdiction to prosecute non-Indian perpetrators.

Morgan specifically credited Operation Lady Justice, one of President Trump’s 2019 executive orders, as a reason why Oklahoma legislators decided to support Ida’s law. Morgan said that before that, people weren’t willing to learn more.

“When we first started working in 2020 — Ida's law was filed as a bill here — not very many people in the Oklahoma legislature knew what MMIP was,” Morgan said. “So, I think that on the federal level, with the Trump administration establishing Operation Lady Justice, that was a leading example.”

The Not Invisible Act is another example of MMIP legislation at the federal level, which established a commission made up of tribal and federal leaders, law enforcement, service providers and individuals directly impacted by the crisis.

The commission published its findings in 2023, and the Departments of Justice and Interior issued a response in 2024. Together, the path to solving the crisis became clear: consistent funding, accountability of medical examiners, culturally sound communication, data coordination and allowing tribes to maintain criminal jurisdiction over their lands, among other solutions.

The findings ultimately pointed blame at the government’s failure to uphold its treaty obligations to Indigenous nations in the U.S. and its harmful policies that disconnected them from their land, culture and language — something Moorehead wrote about more than a century ago.

“When we moved these Indians west of the Mississippi River about 1833, we solemnly promised them that they should remain undisturbed on the land selected by them in Indian Territory. We have not kept that promise,” he wrote in Our National Problem.

Moorehead said Oklahoma representatives pledged to safeguard the rights of American Indians and failed to do so. He explained that the federal government also failed to carry out the same task, a devastating example that played out in Ulteeskee’s conservatorship.

“[W]e, the American people, gave these Indians land in severalty and promised that they should reside upon their farms, homesteads or allotments in peace and security,” Moorehead said. “We told them that they would be protected, even as are white citizens of the Republic. For the third time, we have lied to these Indians.”

Progress has been made in solving the MMIP crisis, but are current efforts enough?

Since Ulteeskee’s lifetime, the MMIP crisis has gained more awareness in the public eye, thanks to advocates such as Morgan. In the past decade, mainstream media has caught on as well as state and federal leaders.

Most recently, Oklahoma Attorney General Gentner Drummond announced the launch of a new state MMIP task force aimed at solving cold cases and preventing new ones, leveraging evolving technology and collaborating with various entities. It builds on the work already done by OSBI and its MMIP liaison office.

Despite these efforts, Morgan still wants answers about her cousin, Ida Beard. She is continuing her fight, leading the Cheyenne and Arapaho MMIP Chapter and sitting on the state’s new task force.

One of her current goals is to improve public safety education. For children and the elderly, that looks like teaching them about potential dangers of social media and games such as Roblox, where strangers may lurk as predators.

Morgan said educating those young folks that they can and need to report abuses and domestic violence is imperative. Some indicators that someone may be in an abusive relationship are: isolation from loved ones, extreme jealousy or controlling behavior of the partner, personality changes and frequent injuries.

“We protect our people, preserve our children, our elders, preserve life,” Morgan said.

For Ulteeskee, her protection came from the Bureau of Indian Affairs, which investigated her situation and later sent a lawyer to sue Harold Lannom. They showed up after Lannom had already gambled much of her money away.

Ulteeskee’s last will, issued in 1950, stated she did not have living relatives, including children. During her probate hearing, her stepbrother, Red Cloud Lannom, told the judge the same thing. It’s unclear if both were intentionally lying.

At the time of her death, her allotment lands were managed by Red Cloud Lannom, with whom she lived for the last ten years of her life, before she had a stroke and passed away in 1960. What was left of her estate — which earned about $800 a year — was given to him.

The crisis that persists today is similar to Ulteeskee’s story. One of the most salient ones Hosmer identified was that Indigenous people are still viewed as wards of the state.

“Even with you know tribal citizenship alongside US citizenship, their property, at the very least, is still managed by the federal government, at least at some level,” Hosmer said.

Jurisdictional challenges, especially in Oklahoma, continue to cause disruptions in solving MMIP cases, as well as ensuring these cases are a priority to law enforcement. Often, to secure justice, someone else has to intervene; today, many are MMIP chapters and relatives. But even then, sometimes the fight for truth and protection is still not enough.

“If an Indigenous woman goes missing today, nothing happens unless something, somebody, does something and even then maybe nothing happens,” Hosmer said.

Allison Herrera contributed to this report, which was supported by Crosswinds Media and the International Women’s Media Foundation’s Fund for Indigenous Journalists: Reporting on Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, Two-Spirit and Transgender People (MMIWG2T).

Special thanks to Cherokee Nation Genealogist Charla Nofire and Veronica Redding for verifying Akey Ulteeskee’s tribal affiliation and providing valuable archival information.