The abduction of Jackson Barnett: What really happened to the “world’s richest Indian”

Photo Courtesy: Library of Congress

Written By: Noel Lyn Smith

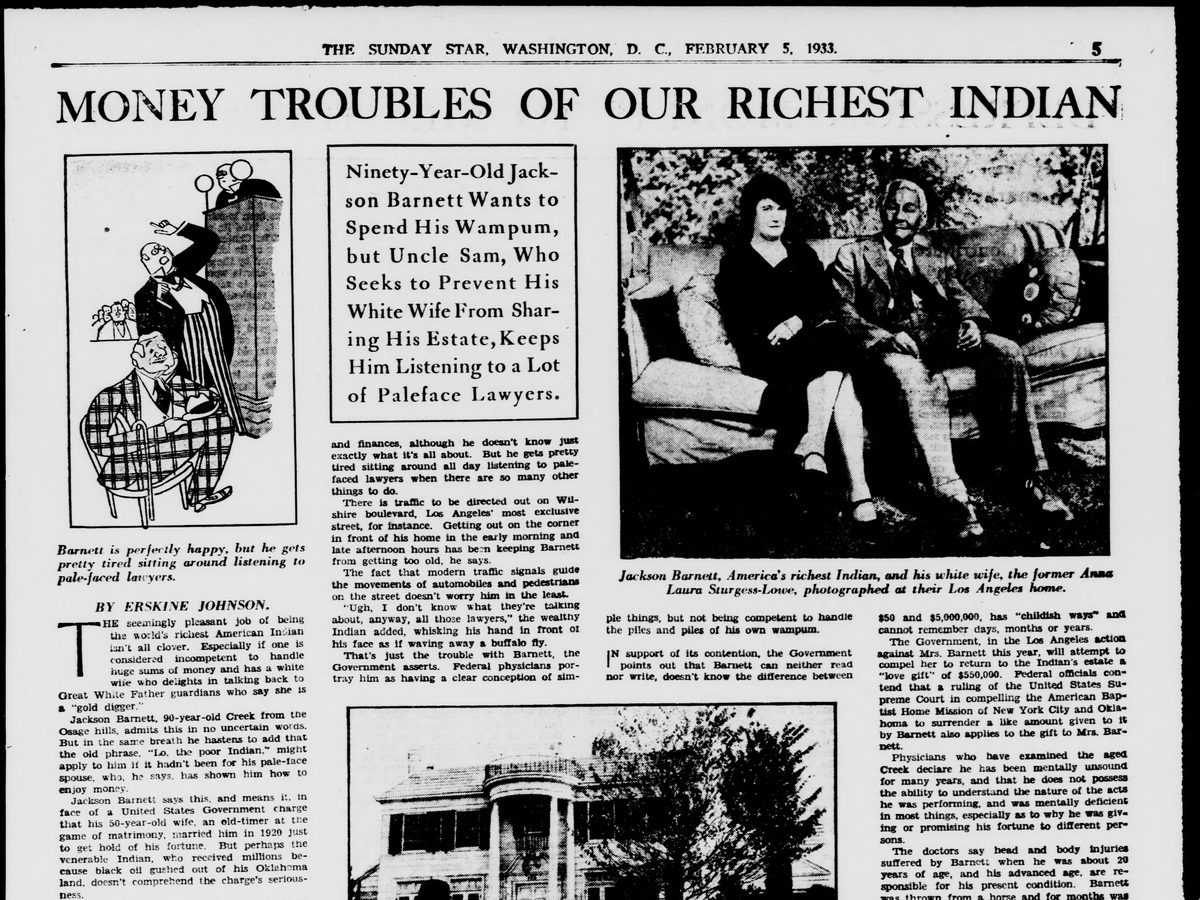

(LOS ANGELES, Calif.) Buried in what is now known as Hollywood Forever Cemetery, Muscogee oil millionaire Jackson Barnett died in California in 1934 at the age of 93 following a 14-year marriage to his alleged kidnapper Anna Laura "Mary" Lowe.

Read Part 1 | Reflecting on an era of fortune and deviousness: The Jackson Barnett saga

A Los Angeles Times story shows his marriage to Lowe was annulled by a federal district court that same year.

Barnett’s estate was estimated at $4 million in cash, securities and real estate in Los Angeles and Riverside County in California as well as in Creek County in Oklahoma, according to Indigenous historian Donald Fixico’s book, “The Invasion of Indian Country in the Twentieth Century: Tribal Natural Resources and American Capitalism.”

His circumstances have been a national debate for decades, and the controversy over his estate continued long after his death.

This reporting was supported by theInternational Women’s Media Foundation’s Fund for Indigenous Journalists: Reporting on Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, Two Spirit and Transgender People (MMIWG2T).

A Legacy of Exploitation

Ronald Barnett views his great-great-great-uncle’s abduction and exploitation as an early example of the disturbing trend that’s become known as Missing and Murdered Indigenous People (MMIP).

“It could have ended up worse,” Ronald Barnett said of his great-great-great-uncle’s life, because many other wealthy Natives in Oklahoma during that time were either murdered or died under suspicious circumstances.

When it comes to Jackson Barnett’s marriage to Lowe, Ronald Barnett said he spoke with other family members about it and many recall how “one day he showed up at the house with her and that was it.”

He said they ran off and were gone for nearly a month, but when they came back they were married.

Other records, such as the 1923 affidavit of R.C. Mason obtained by Tulsa attorney S.R. Lewis revealed sinister plotting in April 1920 to gain Barnett’s estate, including Lowe and her attorney Harold C. McGugin asking Muscogee interpreter C.R. King to kidnap a child to pass off as her own.

“McGugin offered to pay King well for his services if he would steal or kidnap an infant half-breed Indian or Mexican child for the purpose of giving to Mrs. Jackson Barnett so that she could claim a blood heir to the estate of the said Jackson Barnett by swearing that the child so stolen or kidnapped was the lawful child of herself and the said Jackson Barnett,” the affidavit states. “King laughed at the proposition and turned it down and said that could steal him a sack full at a stomp dance at any time, but that he did not want money badly enough to deal in human beings and at that reply McGugin seemed to be vexed and sore.”

Mason stated McGugin said he would be paid hundreds of thousands of dollars if he recovered Barnett’s estate for Lowe, and that he was present while Barnett was held “under lock and key” in Coffeyville, Kansas following his marriage to Lowe.

The affidavit and similar archival documentation of historic wrongdoing are available online through the IRA database at the Tulsa City-County Library.

When the couple moved to California, Ronald Barnett said they left everything behind. However, his great-great-great-uncle’s house still stands outside Henryetta, Oklahoma.

“The people that own it now let me walk through it,” he said. “They were starting to remodel the whole inside of it, so I got to see it the way he lived in it.”

Ronald Barnett said what happened to his great-great-great-uncle is not unique and many Native families have these sorts of experiences as part of their family history. For instance, one of his lawn mowing business customers is an Osage woman, who told him that similar things happened to a relative in her family.

Meanwhile, many relatives of Jackson Barnett have found themselves barred from his land, oil and mineral claims. Others refuse to talk about this history.

“It kind of made me angry about it,” Ronald Barnett said.

A disturbing trend – and response

Advocacy by Native Americans has brought attention to MMIP in the United States. The movement continues to call on federal and state governments to address the crisis by implementing policies, improving data collection and lifting barriers when it comes to services to help family members of missing loved ones.

Oklahoma is among the states that have taken steps in recent years to confront MMIP through new laws and revising procedures to improve how cases of missing Indigenous people are handled.

The National Missing and Unidentified Persons System - a federal database - lists 82 missing person cases for American Indians and Alaska Natives in Oklahoma. In its bi-annual report on missing persons cases, NamUs ranked Oklahoma third for the highest number of cases involving American Indians and Alaska Natives, with Indigenous men comprising 69 percent of them.

“When you start having the discussion of MMIP, to me (it) encompasses a variety of other crimes,” said Dale Fine, a special agent with the Oklahoma State Bureau of Investigation’s Office of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Persons. These other crimes could include homicide or human trafficking, he explained. He said the latter especially concerns tribal communities.

“I think it is kind of synonymous with that,” he said.

Fine’s position as a tribal liaison for MMIP cases was created through Ida’s Law, which went into effect in November 2021. The office is responsible for providing families with resources as well as helping them contend with court hearings. Another aspect of the office is facilitating law enforcement training on issues related to MMIP. It’s named for Ida Beard, a citizen of the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes, who went missing at age 29 in June 2015 in El Reno, Oklahoma.

Terms like human trafficking and MMIP did not exist during Jackson Barnett’s lifetime. Designated resources were also nonexistent for tribal citizens to use when family members were victims of violence, abuse or exploitation.

If Ida’s Law existed when Barnett was alive, his outcome could have been better.

“I think it’s something that would have helped,” Fine said.

This reporting was supported by the International Women’s Media Foundation’s Fund for Indigenous Journalists: Reporting on Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, Two Spirit and Transgender People (MMIWG2T).