From Colonized to Colonizer: Reflections Ahead of America’s 250th Anniversary

The United States of America is a country built by and for colonizers.

Roughly 350 million people will call the United States home when it turns 250 this year. That’s ten times the number of people living here in 1776, which included half a million enslaved Africans. Another 1 million Indigenous people were also here, but excluded from colonial record-keeping.

Despite the well-to-do imaginings of many colonial descendants, historians estimate at least half of the earliest Europeans who immigrated to what is now the US arrived as indentured servants. The percentage of indentured immigrants was as much as 85 percent in southern colonies like Virginia. These servants were often poor people who sold themselves into servitude, but others were tricked and even taken across the Atlantic against their will: homeless people, children sold by their parents, and captured prisoners of war. Most were English, Irish, Scottish and German.

They came here as a last-ditch effort to survive, like so many others today.

Following two and a half centuries of immigration, the United States is now made up of nearly 200 heritage groups, according to the APM Research Lab “Roots Beyond Race” project.

We are a nation made up of 97.4 percent immigrants or descendants of immigrants, a reality that stands in stark contrast to the sweeping, cruel and often violent immigration crackdowns happening across the United States as we approach our country’s birthday.

While the federal government has taken the lead on the upcoming celebration, 1776 was not the birth of the federal government, which didn’t exist yet. In reality, July 4 is the anniversary of the people of the colonies declaring independence from authoritarian rule and asserting the principle of self-government.

The federal government, as we know it, actually began operating in 1789.

An Identity of Colonization

Some other interesting facts about US history. Though Christopher Columbus is celebrated in certain circles as “discovering” America in 1492, he actually never set foot in what is now the United States.

While European colonization of the Americas began during that century, it really got going in the 1500s and 1600s with Spain, France, and ultimately the British. The latter was, of course, the most sustained colonization effort with the establishment of the 13 colonies, including Jamestown, Virginia, in 1607 and Plymouth, Massachusetts, in 1620.

Having lived in Massachusetts from 3 to 21 years old, this is the history I remember learning about in school. The colonists were praised for fighting back against the wretched British and Thanksgiving was a months-long celebration. We fieldtripped to Plymouth Rock. I knew all about the Minutemen, throwing tea in the Boston Harbor, and can still recall the life and struggles of the fictitious Johnny Tremain.

These were the first clues to understanding my cultural identity.

Like many others who grew up in the Greater Boston area, some of those early 1600s colonists are my ancestors. Some fought in the Revolutionary War. This was history I connected to and took pride in. As much as a troubled poor kid from the Northshore takes pride in something like that, anyway.

It wasn’t until I turned 20 that I started getting into genealogy and learning more about my other ancestry lines. Over the last 18 years, I’ve uncovered a lot about who my people were, dating back to this country’s earliest days, and where they likely lived during the birth of our nation. And, perhaps most importantly, I’ve grown to understand why this knowledge matters so much.

When the Colonized Becomes the Colonizer

About 3/4 of my great-great-great-grandparents were living in the US during the mid 1800s. They were Irish, Scottish, English, and, almost entirely on my father’s side, Scots Irish.

My remaining ancestors were still living in Ireland (4) or Mi’kma’ki/Nova Scotia (5), both of which were colonized by the British.

Now, I’m not sure honestly where I get it from, be it my Irish ancestors who moved to the US in the late 1800s or my Acadian/Mi’kmaq ancestors who moved to the US in the early 1900s. Maybe it traces back to the English invading the Scottish Lowlands in the mid-1500s, which eventually led to the migration of my Scots-Irish line. Or maybe it’s just the human in me.

Perhaps it was moving to Oklahoma 15 years ago and learning the truth about Indian Country. But I am fiercely against colonial harm, and constantly pondering how to undo it.

It’s quite a conundrum for someone who is also descended from colonizers.

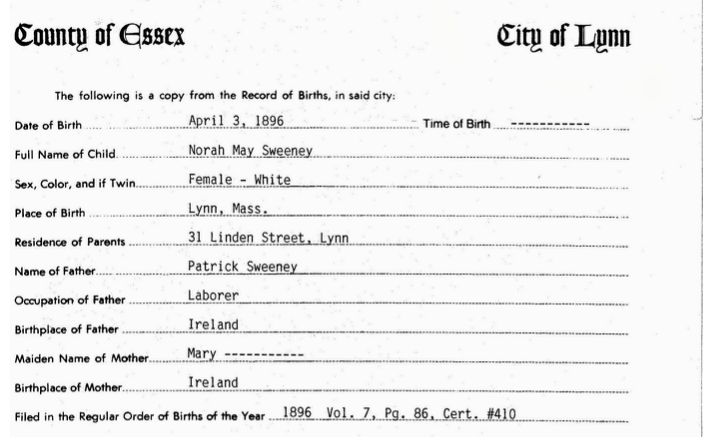

Growing up as a pale, freckly redhead in the Greater Boston Area, I always knew that I was an Irish American. My great-grandmother Norah, on my mother’s side, was the first in her family born in the United States after her parents came over from Ireland.

Irish immigrants often took dangerous, low-paying jobs, building infrastructure like canals and railroads, while facing extreme discrimination and prejudice. And bad behavior wasn’t just vertical, of course. Injustice also moved sideways, as it often does, opportunity corrupting those within the community, right alongside the power holders of the established resident hierarchy.

Talks with my maternal grandmother, Helen “Nana” Clements, about growing up outside of Boston in the 1930s are both the most cherished and heartbreaking discussions I’ve had.

Nana became a ward of the state at age 2, when her mother Norah died of tuberculosis and her father couldn’t care for her and her siblings anymore. She survived several foster homes as a ward of the state, as well as a long-term stay in a sanatorium, treated for tuberculosis after she was hit by a car.

She described it as the best years of her childhood.

“That was the best place I lived because we had swimming and we did all kinds of things,” she told me. “We had to work, too, but we had swimming and we had movies on Wednesdays and ice cream, and I learned to swim and I learned a little skiing and stuff like that. Just a little hill in the back of the hospital. So it was good.”

At the time of her accident, Nana was living in a room with four other foster girls, likely kept to “help with the finances.” When company would come over, her foster mother made her and the other girls dance Irish jigs.

But the truth was, they were starving. Nana didn’t remember eating meals at all. Instead, she remembered the older girls stealing chocolate and coconuts from the store to survive.

“At Christmas time, there'd be a whole lot of presents under the tree and everything,” Nana said. “And then the next day we would get up and everything would be gone. So she took all the Christmas stuff back.”

Her last foster home was better, an Irish foster mother with an adopted daughter. She also worked harder than she ever had before, starting at just 11 years old, doing all of the household chores while also working outside of the home.

“But you never felt loved,” Nana said. “I mean, I never felt loved in any of the homes I was in. So it was hard. It was hard if you found somebody. I could never say ‘I love you’ because you didn't know what it felt like.”

The Downsides of the American Experience

Like so many of my ancestors and relatives, I didn’t have a comfortable upbringing.

My identity was largely tied to poverty, abuse, and neglect. As a single parent, my mother was forced to work long hours for much of my childhood. She strived to provide my twin sister and I with a two-parent household. Unfortunately, her partners during most of our childhood were abusive and neglectful.

I was also identified as a problem child. As my home life worsened, so did my developmental delays. Children experiencing trauma at home go to school in survival mode, unable to focus and learn, often displaying challenging behaviors. Looking back, I can see I was a prime example of this. At the time, I just thought I was dumb because my brain couldn’t process what I was being taught.

It never felt like I belonged anywhere. I was disconnected. I felt unwanted. After being court-ordered to attend school, I dropped out.

Culture meant nothing to me. We celebrated federal holidays, my sister and I, not understanding that most mainstream holiday traditions were a hodgepodge of the cultures of immigrants over hundreds of years, including that of my own ancestral cultural heritage. Don’t get me wrong- I loved the holidays. It was one of the few times of the year that I experienced true joy. My mom always made sure they were very special. But celebrating a handful of holidays every year was far from being culturally nourished. Especially when you don’t even understand where they come from.

My concept of American culture worsened over time. As a poor kid, later a poor adult, at best ignored and at worst abused by people in power, mainstream American culture just really didn’t sit well with me.

I was burned by individualism. If it’s so good, then why does 1 percent of the U.S. population control nearly one-third of the country’s wealth? Why are so many others destroying themselves to catch up or just survive? Why do we heap on the societal work of what used to be a whole community onto just two people, or worse, a single parent? It’s no wonder nearly half of Americans experience significant daily stress, with work-life balance, childcare costs, and the housing market stressing millennials like me out the most.

I was sick and over consumerism. Why is it so acceptable for advertisers to feed our insecurities, then hype their product or service as the cure? Why are things no longer built to last, despite resources on our planet being so limited? Sold without a thought of where they come from, or who made them?

Long story short, my broad strokes American identity felt manipulated, destructive. And lonely as hell.

Ironically, I was not alone in that. After decades of increasing isolation, loneliness was declared a public health epidemic in the U.S. in 2023. A key finding? Lacking social connection can increase the risk for premature death as much as smoking up to 15 cigarettes a day.

I moved to the south and met my husband, a Muscogee Nation citizen with Cherokee lineage. A biracial Native with Irish ancestry, he’s also helped me understand secondhand just how particularly hard the loneliness epidemic and other mental struggles can be for multi-racial people.

While conducting research on Native American health disparities, I came across the 2023 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. The stats on multiracial people were staggering.

Among adults 18 or over, multiracial adults were the most likely to have mental illness compared to all other racial or ethnic groups (36.7 percent). Multiracial adolescents led with the most major depressive episodes the previous year (24.4 percent). And multiracial adults were the most likely to have had a serious mental illness in the past year (14 percent), more than twice as likely as other races. Multiracial adults and adolescents also struggled with suicide the most.

When I shared this information with my husband, he said he already knew that.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, I discovered the Great White Paintbrush.

During my last 15 years in Oklahoma and Texas, I have heard people dismiss their European ancestry as “boring old English” and BIPOC community members call white people “plain old white.” Both are swirling around the same poison.

Covering up the diversity of European American heritage with the Great White Paintbrush further strips people of their identity. It disconnects them from the hundreds and thousands of years that made them who they are and the people who made their existence possible. From the hard lessons and fruitful experiences that are their birthright.

Yes, there were stuffy old English people. But let’s not forget, the English also overthrew the monarchy for 11 years during the 1600s. Our ancestors laughed and cried and lived and died so we could exist.

And again, who does painting every European American with a Great White Paintbrush benefit the most?

Reconnecting to Pre-Colonization Culture

Researching my family history over the past couple of decades has not only helped me, it has healed me. Every story, happy and sad, connected me to generations of people who made me who I am today. These connections have slowly but surely filled the gaps in my identity, helping me to understand my own mind and inclinations, and have even helped to deepen my relationship with the natural world around me.

Humans have existed for hundreds of thousands of years. This American existence, just shy of 250 years, is barely a blip on the map.

Evolutionary adaptations, such as how our bodies work, how they respond to stress and the environments around us, are learned and passed on through our DNA. That means adaptations that developed before modern society still influence human behavior today.

It’s one of the reasons so many people are still pulled to community, to belonging, despite American society’s constant push for individuality, for separation. For roughly 95 to 99 percent of humanity’s 300,000-year history, humans lived in small, interdependent communities. Even today, an estimated 85 to 90 percent of the world’s population lives in community-centered societies.

It’s only been over the last 500 to 700 years or so that something different began to take shape.

Which brings us to Western culture, which is arguably the most disconnected and unbalanced kind of society, a conclusion underscored by the WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic) field of study. WEIRD research shows these cultures are behavioral outliers, oddities in their individualism and detachment from land and community compared to the rest of the world.

In a disconnected society, pain is often an isolated and unhealed experience. Given how many of our ancestors experienced painful trauma relating to colonization, it’s no wonder that reconnecting to pre-colonization culture and ancestral knowledge can be a powerful tool for healing.

When I traveled to Ireland for the first time in 2017, it felt like coming home.

Fast forward to 2019 and the birth of my son. My ancestral journey intensified. Wading through my husband’s generational trauma, saddled with my own, I knew I would do anything to give my son a less traumatic, more connected life.

Part of our journey at Crosswinds News has been understanding historic and generational trauma, and the most effective ways to heal from it. We’ve talked with clinical social workers who practice somatic therapy, in which people physically work through their trauma. We’ve interviewed experts who have found that strengthening cultural identity in Native youth can lower suicide risk later in life.

So, in addition to supporting my family’s reconnection to their Muscogee culture, assisted by Tribal elders and resources, I’ve also been helping us reconnect with our Irish heritage through volunteer work at the Irish American Club of Tulsa and forging connections overseas.

My journey to Mi'kma'ki this past winter was the last piece to my ancestral heritage puzzle.

Mi’kma’ki is the ancestral homeland of the Mi’kmaq Nation. It spans what is now Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, New Brunswick, parts of Quebec, and Newfoundland.

After coming to what is now Nova Scotia in the 1600s, my Acadian ancestors lived and intermarried with the Mi’kmaw people there. These allies joined forces to fight off the English and later the British, but ultimately lost the fight. The British committed genocide against the Mi’kmaw people and deported the Acadians.

According to the Mi’kmawey Debert Cultural Centre, the Mi’kmaw economy was based on sharing and reciprocity. Social status was measured not by what a person had, but by how much they gave to others and how deeply they were connected to the natural world.

This resonated with me, profoundly.

Ahead of my trip to Mi’kma’ki/Nova Scotia, I talked with Shannon Monk, a member of St. Theresa Point First Nation in northern Manitoba, an Anishininew fly-in community. Shannon also has Mi'kmaq roots from Lanark Island and Celtic roots from the eastern shore of Nova Scotia. She is the cultural tourism project manager for Kwilmu'kw Maw-klusuaqn, the Assembly of Nova Scotia Mi'kmaq Chiefs.

When I brought up the notion that Canada appeared to be ahead of the US in regard to Indigenous relations, her response was akin to “not quite.”

My assumption of the friendlier Canadian neighbor deflated.

“Canada has a ways to go,” Monk said. “I think what's happening in the States is absolutely disgusting. I don't know if it's just more visible in the States, but I would say that we still have a long way to go in Canada. We're nowhere near where we need to be by any stretch of the imagination. And that's why the Mi'kmaq Rights Organization exists and why all of the other rights-based organizations exist all across the country.”

She told me some Mi’kmaq communities received running water in just the past 10-20 years, and others still experience third-world conditions.

When asked about how people like me can reconnect to Mi’kmaq culture and support communities connected to our ancestors today, Shannon referred me to some resources (such as the incredible Millbrook Cultural and Heritage Centre), but reminded me that community members can be wary of those reconnecting, as there are always those looking to take instead of give.

“From a reconnection standpoint, there's a difference between a genuine interest in reconnecting and then there's like, okay, I'm going for my status card so I can get in there and get all the free stuff I'm entitled to,” Monk said. “And I'm being obnoxious to prove a point.”

Living in Oklahoma, home to 39 tribes, this was a reality I was unfortunately already familiar with. People viewing tribes as cash cows, focused more on how they can profit from connection instead of how they can support it.

“It’s really sad,” Monk said. “I mean, welcome to colonization and mission accomplished. In terms of that eradication of culture and pride in identity, a shift is happening. But I think we're only at the beginning stages of that shift. We're only 10 years into that shift. So, we have, according to the seven generation teachings, generations to go before we get that all reestablished. But we have to start somewhere.”

Reconnecting to pre-colonization culture has been a radical and powerful tool for bettering my own life, awakening my long-sleeping identity and driving a newfound sense of belonging. So, I can’t help but imagine what could happen if we were all more connected to the centuries of cultural heritage taken from our ancestors? If we were balanced back to community, and less isolated from each other? If we were more focused on what we can give, instead of what we can take?

More healing, less suffering. More room for the wonder of nature and appreciation of one another, less destruction of our planet and fear of one another, and of ourselves. Improved understanding of who we truly are.

I’m not saying we have to throw the whole book of American culture away. That individuality should be avoided at all costs. That we should cancel all consumer culture. What I am saying is America has a balance problem.

The first 250 years of the United States has proven we can do great things, but also terrible, self-destructive things.

True patriotism is not blind allegiance to a flag; it is the steadfast pursuit of a country that lives up to its people and its ideals. To achieve this, we must fully acknowledge and address the harmful impacts colonization has had and continues to have. We must begin to prioritize the importance, the success, the power of the whole, as well as our unique connections to that whole, to the land and to each other. We must find balance.

Without it, we are unfinished. An illusion of overall success. Always falling short of fully realizing our power and potential as a country and rarely achieving the peace and comfort of knowing our true selves.

Thank you to the many people who interviewed with me for this editorial, especially my Nana Helen. Thank you also to the Tiny News Collective "Spark Fund" for supporting my research trip to Nova Scotia, which helped inform this editorial. Finally, thank you to my dear friend Shannon Shaw Duty for editing this editorial and giving me the final push of confidence to publish it.