Relative of neglected Native girl uncovers pattern of atrocities and greed in Oklahoma

(MCCURTAIN COUNTY, Okla.) For 79-year-old Richard Johnston, retirement from his career as a computer programmer hasn’t led to a quiet life off the clock. The Choctaw citizen has honored his love of history by researching and investigating cases of Native minors who found themselves both in sudden wealth and at the mercy of their guardians.

Johnston lives in Atlanta and started his research in the 1980s.

“My mother and I would drive out to the archives in Fort Worth, Texas, they have a lot of Choctaw records down there,” said Johnston. “Now they got them online. Just about everything I had to go out and get from Fort Worth and other places.”

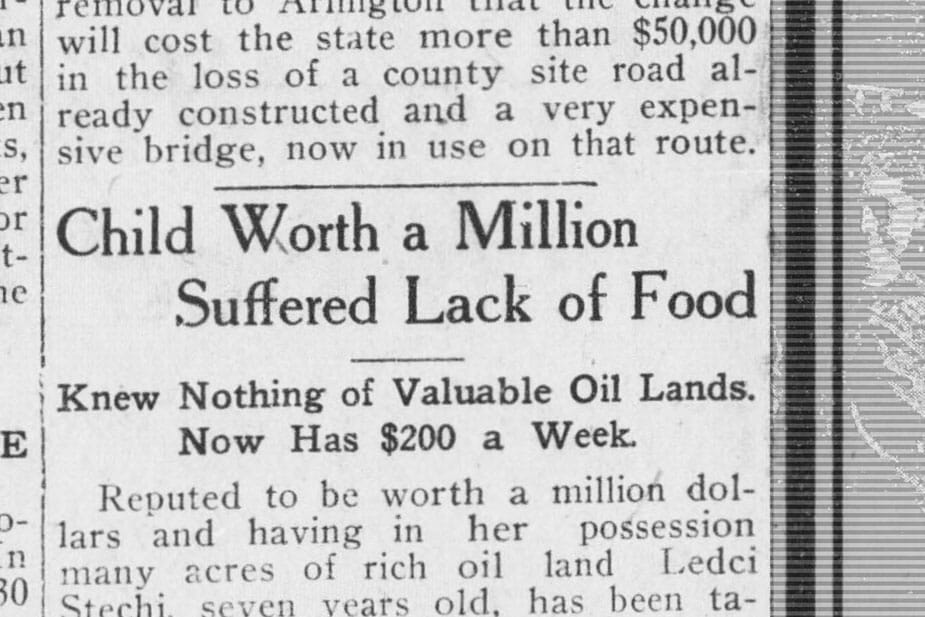

One of the cases he’s researched is that of Ledcie Stechi, a full-blooded Choctaw minor who died in August of 1923 after allegations of neglect by her white guardian, W.J. Whiteman. She was only seven years old.

This reporting was supported by the International Women’s Media Foundation’s Fund for Indigenous Journalists: Reporting on Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, Two Spirit and Transgender People (MMIWG2T).

For Johnston, the quest for answers in this sad case is also personal: he’s a third cousin of Stechi.

Johnston said one of the things that intrigued him about her story was the background and personal life of Whiteman. Prior to becoming Stechi’s guardian, Whiteman was already wealthy and, according to the McCurtain County Historical Society, married to the daughter of Henry C. Harris, chief justice of the Choctaw Supreme Court.

“I assume he did that because he wanted to make some money off of [Stechi] because of her mother’s oil that she inherited, and the oil land that her mother had,” explained Johnston. “And he just lost interest in her or something, didn’t take care of her.”

Johnston said one of the saddest things about Ledcie’s situation was how little Whiteman gave her to live off when she was still living with her grandmother.

“They (Ledcie and her grandmother) were living off like $10 a month,” said Johnston. “They were starving to death.”

According to an account recorded by the Indian Rights Association in 1924, Stechi weighed only 47 lbs. at the time of her death. Her living conditions - described as a “small and poorly ventilated house, surrounded by filth and dirt” - never improved, nor did Whiteman express any interest in her personal well-being, health or education.

A letter written by the Choctaw National Attorney E.O. Clark in October of 1923 states that some aspects of Stechi’s condition at the time of her death gave people a reason to be suspicious.

“The vomiting, diarrhea and blackening of the lips of the child we are advised, are symptoms of poisoning, and specially of mercurial poisoning,” wrote Clark.

According to Clark’s letter, the doctor who had treated Ledcie also refused to turn over any records of prescriptions he had given her while she was ill.

As a relative of Ledcie, Johnston said learning about what she went through has had an impact on him.

“This is terrible and you see that picture of her you know and you're like that poor kid didn't stand a chance,” said Johnston.

Through his research, Johnston said he hoped people do not forget what happened to Native children like Ledcie. He manages a Facebook page, “Choctaw Woman - Mela Comes Home” where he shares some of his research with followers.

Johnston has used the page to share clips from articles he has found about Ledcie’s case and many others, where opportunists wormed their way into Native people’s lives to get access to their fortunes and local officials either turned a blind eye or were in on the corruption.

“People don’t understand they ruined lives,” said Johnston. “They pushed Indians almost to the brink of extinction.”

Johnston’s research also found that Zula Breeding, a federal employee and the superintendent for Wheelock Indian Boarding School, attempted to cash in on part of Stechi’s estate following her death.

According to an article from The Morning Tulsa Daily World Sun published on March 30, 1924, Breeding contacted Nellie Stechi, Ledcie’s grandmother, and Ruth Bohananan, her half sister, in an effort to graft from the estate.

“Mrs. Breeding permitted the older woman to enter into contracts with two attorneys.” read the article. “Each of which gave the lawyer fifty percent of Ledcie’s estate, which was estimated at $500,000.”

According to the Bureau of Labor Inflation Calculator, $500,000 in August of 1923 would amount to nearly $9.5 million today.

Breeding’s attempt was aided further by the fact that one of the attorneys was her brother.

“He gave himself 50% of the oil money, you know, that was his fee for handling the transaction,” said Johnston.“The whole estate. He took half of it.”

But Breeding’s attempt got her in trouble. An article from the May 27, 1926 edition of The Muskogee Times Democrat reported that she was fired from her position at the Wheelock Indian School.

Johnston believes Breeding tried sending a check to the U.S. Department of the Interior.

“Where they were keeping all the records for the kids' money,” he said. “The guy there, he says, ‘We're not gonna give you that money. We're not, definitely not gonna give half of the estate to your brother.’”

Breeding was indicted because of her involvement in a check being drawn on the account of an Indian minor.

Johnston said throughout his research, he’s found other attempts to take advantage of Native Americans with money in that era.

“Anytime they had land, land with oil on it, they were either killed or extorted,” said Johnston.

A campaign of coercion, deceit and murder

Tragically, the 1920s were an unfortunate time for Native Americans of other tribes in Oklahoma as well.

What’s become known as the Osage Reign of Terror took place in the 1920s. Many members of the Osage Nation had land with valuable oil resources on it and at least two dozen turned up dead under mysterious or suspicious circumstances.

According to the FBI, Anna Brown was the first Osage Citizen to turn up dead when her body was found in a ravine in northern Oklahoma in May of 1921. An undertaker discovered a bullet had been fired into the back of her head. In the next two and a half years, five of Brown’s relatives - including her mother - would also die in unusual and often violent ways.

As with other Native Americans who died mysteriously during the Allotment Era, the murderers of the Osage Citizens were motivated by receiving money from the victim’s oil royalties.

The FBI says a powerful and affluent cattleman, William Hale - known as the “King of the Osage Hills” - was the leader of this cruel and sinister campaign.

The newly-formed Bureau of Investigation (later known as the FBI) sent detectives to pursue and reveal the truth behind the deaths. Eventually some of Hale’s key conspirators confessed to their roles, and that Hale was the one who ordered the killings. He was sent to prison in 1929 for his role in the Osage Murders.

However, he did not serve out that life sentence. To the surprise and outrage of many in the Osage Nation, Hale was granted parole in 1947. The FBI is said to have kept an eye on Hale, who reportedly worked odd jobs until dying in a Phoenix nursing home at the age of 87.

This bloody saga was told in David Gran’s historical novel “Killers of the Flower Moon”, which was later turned into a movie by Martin Scorsese in 2023.

A crime with a victim but no culpability

Investigative reports and several articles from the time of Stechi’s death mention that she had been neglected, and was very ill and malnourished.

Despite investigative reports and several articles from the period outlining Stechi’s brief but tragic life, Crosswinds News has not found evidence that anyone was ever held accountable.

Johnston found the events after the girl’s death to be upsetting as well.

“That was a sad time and then of course they were preparing for her funeral and they were fighting over who was going to represent the estate now that she was dead,” said Johnston.

As for Whiteman, a Facebook post from the McCurtain County Historical Society said he suffered a debilitating setback eleven years after Stechi’s death. “The great depression broke W.J.” reads the post. “He died in relative poverty in 1934, his business empire gone.”

While the work of researching the history of what happened to Choctaw citizens, Osage citizens and other Native Americans can be time consuming, Johnston says there is always more to look into.

“Well I’m about to quit because I turn 80 this coming April,” said Johnston. “I’m kinda tired, but every time I see an article it just interests me. I write it down or put it in a paragraph, story form. It’s just in the genes because my dad’s father was a minister. But he was also called a walking encyclopedia.”

Johnston hopes others will learn from this history and prevent future injustice.

“The old saying is true, so if you don’t wanna repeat it, you learn about it and recognize it when it happens and do something about it.”

This reporting was supported by the International Women’s Media Foundation’s Fund for Indigenous Journalists: Reporting on Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, Two Spirit and Transgender People (MMIWG2T).